The Great Gulf

(Amos 6:1a,4-7; 1Tim.6:11-16; Lk.16:19-31)

In today’s Gospel, Jesus gives us the story of a well-dressed, well-fed rich man, and Lazarus, a poor, sick and hungry man.

It’s a confronting parable about two lives that never quite connect here on earth, and a chasm that cannot be bridged in the afterlife.

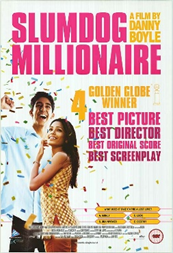

To some, it might seem like an ancient story, no longer relevant to today. But if you’ve seen anything of the poverty in places like Gaza, if you’ve seen the movie Slumdog Millionaire, you already know the world of Lazarus. You know that there’s a great gulf between those who feast and those who suffer.

In this parable, Jesus doesn’t name the rich man. He only tells us that he’s wealthy, comfortable and blind to the obvious. But we do know the poor man’s name. It’s Lazarus, which means ‘God helps.’

The rich man’s sin isn’t cruelty; it’s indifference. He simply doesn’t see Lazarus, so he does nothing to help him.

Then death follows, and a reversal. Both men die. Lazarus goes up to heaven, the rich man finds himself in hell, and a great chasm has opened up between them. Jesus says this is ‘so that no one can cross from there to us.’

In many ways this story is mirrored in Danny Boyle’s movie Slumdog Millionaire (2008). It tells the story of Jamal, a boy from the slums of Mumbai. Orphaned, beaten, cheated, and exploited, he survives by his wit and his courage.

He is a modern Lazarus: ignored by the powerful, abused by society and left to survive as best he can.

What makes this story so powerful is that Jamal remembers. Every question he answers on the TV game show isn’t because of luck; it comes from a painful memory: his mother’s death, sleeping in a filthy toilet, escaping human traffickers.

Each answer is paid for in suffering. And when he finally wins – not just money, but also the dignity of being seen and heard – it’s not just a personal triumph. It’s a reversal, like Lazarus being lifted up.

And those who exploited him: the slumlord, the police, and even the show’s host, are like the rich man in the parable. Their comfort comes at the cost of others’ suffering. And their sin is always the same: they just did not see.

Why does Jesus give us this parable? It’s to wake us up.

The rich man is horrified to find himself in hell, and asks for Lazarus to warn his brothers. But Abraham replies, ‘They have Moses and the prophets; let them listen to them.’

We, too, have the Gospel, the saints and the images and voices of the poor to warn us. But are we listening to them?

We cannot say, ‘I didn’t know’ because Lazarus is all around us – people suffering in silence, at our gates, in our streets and on our screens.

We know that Lazarus is out there. We also know that that great chasm doesn’t start after death. It’s already here, when we fail to bridge the gap between poverty and wealth, indifference and love.

Someone who was deeply moved when he heard this parable was Albert Schweizer, who was born in France in 1875. He was a university professor in Vienna and one of the finest concert organists in Europe.

This parable changed his life. It reminded him of the poverty and disease of colonial Africa, and the need for urgent medical care.

Hearing that the conditions in Gabon, West Africa, were particularly dire, he famously said, ‘I no longer needed to search for my path.’

He abandoned his career and studied medicine. When he graduated, he established a hospital by the jungles in Lambaréné, in Gabon, with his wife Helene. She was a trained nurse and together they devoted their lives to offering medical care for the poor in truly awful conditions.

And through his philosophy of Reverence for Life, he made a significant contribution to ethical thought and practice.

Albert Schweizer gave people hope and joy, and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952.

The movie Slumdog Millionaire ends on a note of hope and joy, too. But Jesus’ parable doesn’t. It ends with a warning: Don’t wait.

Don’t wait until it’s too late. Don’t wait until that great gulf between rich and poor, between heaven and hell, can no longer be crossed.

Who is Lazarus in your life?

And what can you do to help?